The Economics of Scarcity: How Water Stress Shapes Comparative Advantage in Global Trade

Introduction

Water is a fundamental input in nearly all production processes, yet it has historically been underpriced and overused. As climate change alters precipitation patterns and increases the frequency of droughts, water scarcity has become an increasingly binding constraint for many economies. Understanding how water conditions shape international trade is therefore critical, particularly for countries specializing in water-intensive industries.

Debaere (2014) extends the Heckscher–Ohlin framework by treating water as a factor of production and finds that water abundance provides a modest source of comparative advantage. While informative, this approach emphasizes long-run endowments rather than sustainability constraints. It does not capture situations in which countries possess water resources but face severe stress due to over-extraction or inefficient allocation.

This paper – written in collaboration with Juliette Mennicken and Charis Lu of The University of British Columbia – extends Debaere’s framework by shifting the focus from water abundance to water stress, defined as freshwater withdrawals relative to renewable supply. Rather than asking whether water abundance promotes exports, we examine whether water stress penalizes export performance in water-intensive industries. By doing so, we reframe water from a source of advantage to a constraint on trade competitiveness.

Contribution to the Literature

This study contributes to two strands of literature. First, it builds on the trade literature that treats natural resources as factors of production in determining comparative advantage. Second, it connects to the environmental and water-economics literature, which has traditionally focused on domestic allocation rather than international trade outcomes.

While the virtual-water literature documents that trade implicitly reallocates large volumes of water across countries, it largely lacks a formal comparative-advantage framework. Conversely, water-economics research emphasizes scarcity and sustainability but rarely links these constraints to export specialization. By introducing a continuous measure of water stress into a structural trade model, this paper bridges these literatures and provides a more policy-relevant assessment of how water scarcity shapes global trade patterns.

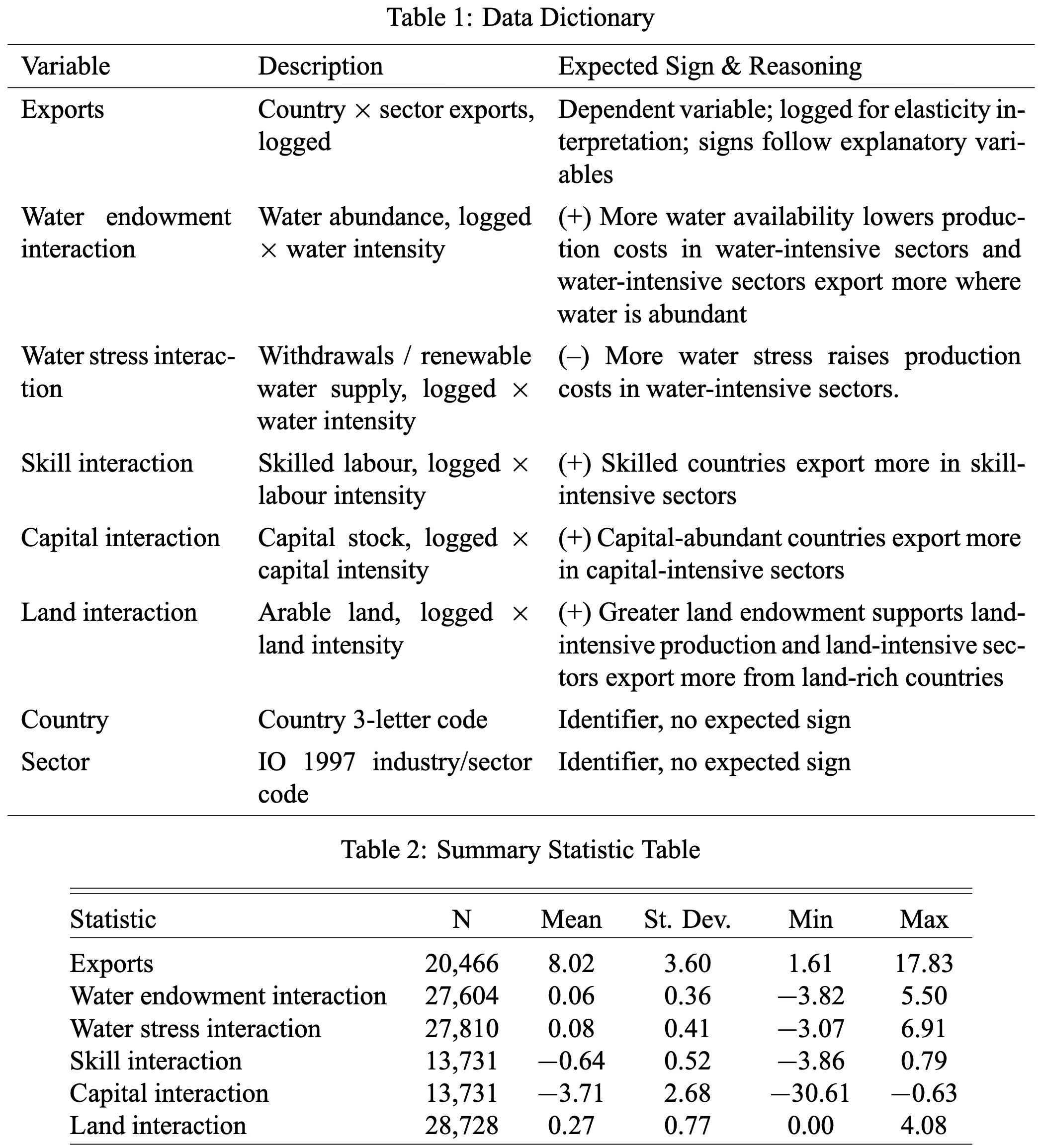

Data and Variables

The analysis uses a cross-section of country–industry data originally compiled by Debaere (2014), covering 68 countries and 196 industries, yielding 11,465 observations. The dependent variable is logged exports by country and industry.

We construct interaction terms between sectoral factor intensities and country-level endowments for water, capital, skilled labour, and land. For the extension, water endowment is replaced by water stress, measured using FAO AQUASTAT data as freshwater withdrawals divided by renewable water supply. This indicator is logged and interacted with sectoral water intensity to capture how scarcity affects water-intensive production.

All variables are log-transformed to allow elasticity interpretation and to reduce the influence of extreme observations.

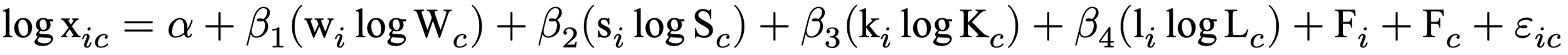

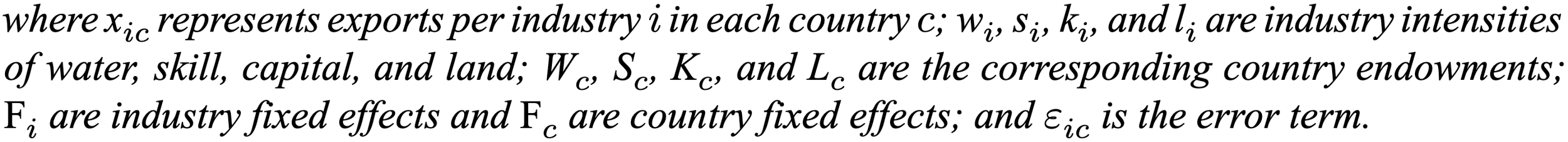

Empirical Framework

We estimate a log–log fixed-effects model of exports at the country–industry level. The baseline specification mirrors Debaere (2014):

The extension replaces water endowment with water stress:

This specification isolates the effect of water scarcity on exports in water-intensive industries while preserving comparability with the baseline model.

Results

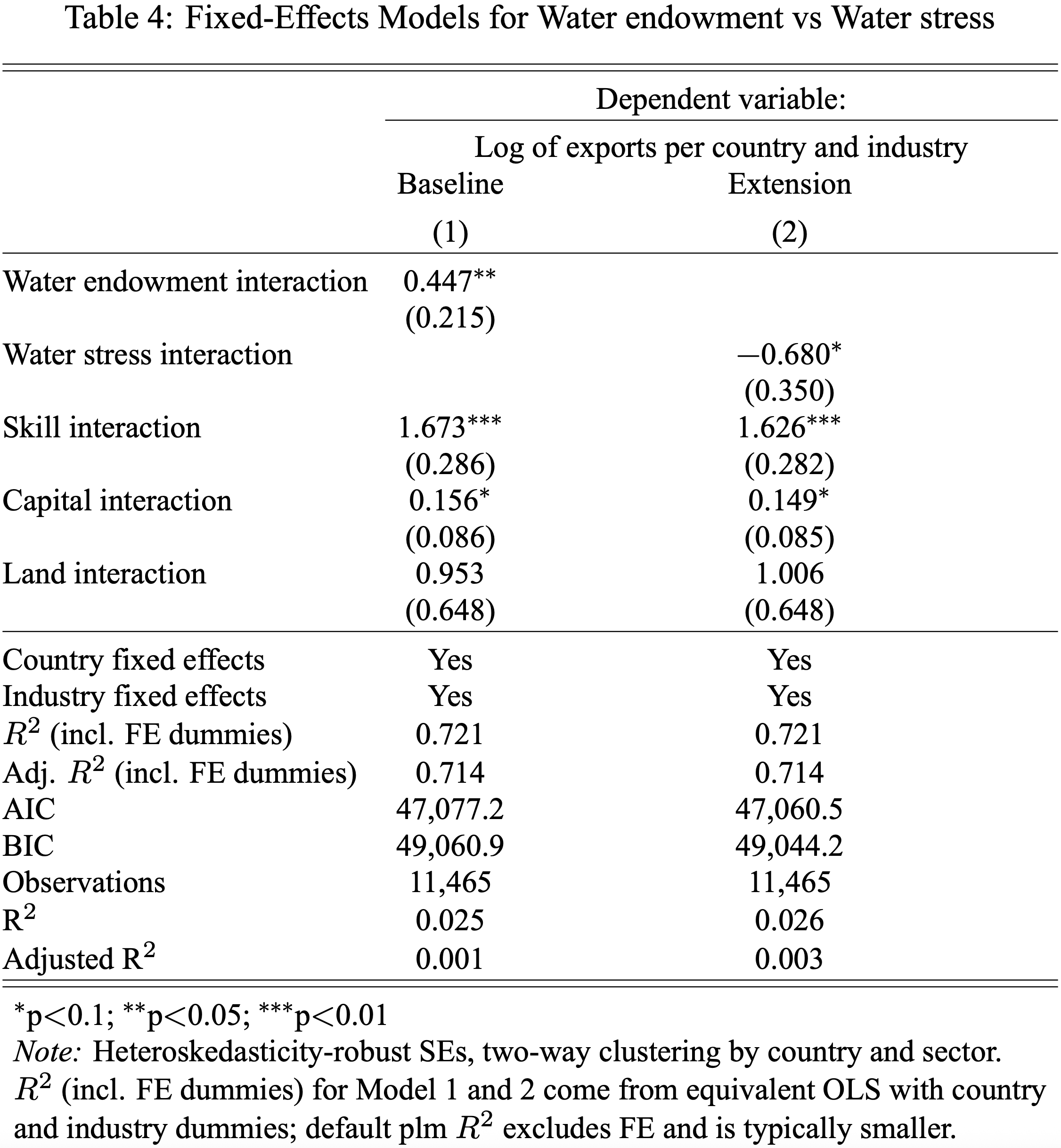

The baseline replication confirms Debaere’s findings. The water-endowment interaction is positive and statistically significant, indicating that water-abundant countries export slightly more in water-intensive sectors. However, the magnitude of this effect is modest relative to capital and skill interactions.

In contrast, the extension yields a markedly different result. The coefficient on the water-stress interaction is negative and statistically significant, with an estimated elasticity of approximately −0.68. This implies that a 10 percent increase in water stress is associated with a 6.8 percent reduction in exports from water-intensive industries, holding other factors constant.

Skill and capital interactions remain positive and strongly significant across specifications, indicating that water stress constrains trade even when other production factors are favourable.

Robustness and Diagnostics

We assess robustness using heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors clustered by country and industry. Variance inflation factors indicate no severe multicollinearity among the main regressors, aside from moderate correlation involving land, which is expected given its overlap with agricultural intensity. Excluding the land interaction does not materially affect the estimated water-stress coefficient, which becomes slightly more precisely estimated.

Additional diagnostics, including Cook’s distance and alternative specifications, confirm that the results are not driven by outliers or influential observations.

Policy Implications

The findings suggest that water scarcity functions as a binding constraint on export competitiveness in water-intensive sectors. Countries facing high or rising water stress may therefore need to reconsider trade strategies that rely heavily on water-intensive production.

More broadly, the results underscore the importance of water pricing and allocation policies that reflect scarcity. As climate change intensifies water stress in many regions, the trade penalties identified in this analysis are likely to become more pronounced, reinforcing the need for adaptation and structural adjustment.

Conclusion

Our paper reframes water from a passive endowment to an active constraint in international trade. While water abundance provides only a modest comparative advantage, water stress imposes a substantial penalty on exports in water-intensive industries.

By integrating a sustainability-based measure of scarcity into a structural trade framework, the analysis demonstrates that environmental constraints already shape global specialization patterns in economically meaningful ways. Future research incorporating panel or sub-national data could further illuminate dynamic adjustment and adaptation, but the core result is clear: scarcity constrains trade more forcefully than abundance enables it.