Who Trades Business Services: A Structural Gravity Model Perspective

International trade in business services offers a clean lens through which to study the forces shaping global integration. Unlike goods, services trade depends less on physical shipment and more on information flows, institutional compatibility, and economic scale. In this project, I applied a modern gravity-model framework to bilateral business services trade, using a rich cross-country dataset to disentangle how distance, economic size, shared characteristics, and policy membership shape observed trade patterns.

The analysis follows the empirical structure outlined in Shepherd, Doytchinova, and Kravchenko (2019), but shifts the focus from aggregate services to the Business (BUS) sector, allowing for a more targeted interpretation of how high-value services are exchanged across borders.

Who Trades Business Services?

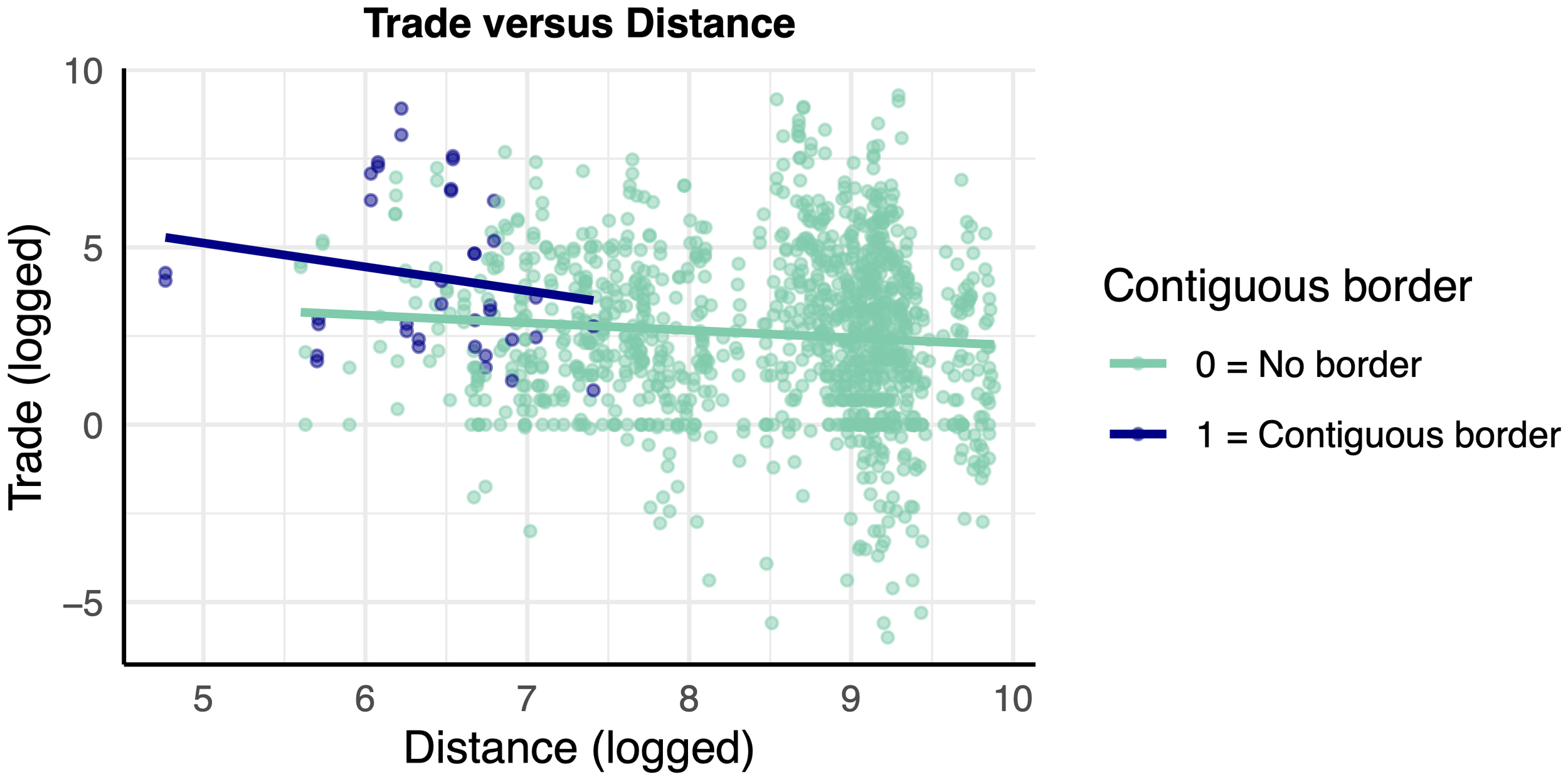

The 2005 dataset I used includes 78 countries, all of which recorded positive exports of business services. However, while participation was universal at the country level, trade relationships were far from complete. Only about 50% of undirected country pairs and 45% of directed pairs exhibited non-zero trade flows, highlighting the sparse and selective nature of services trade networks.

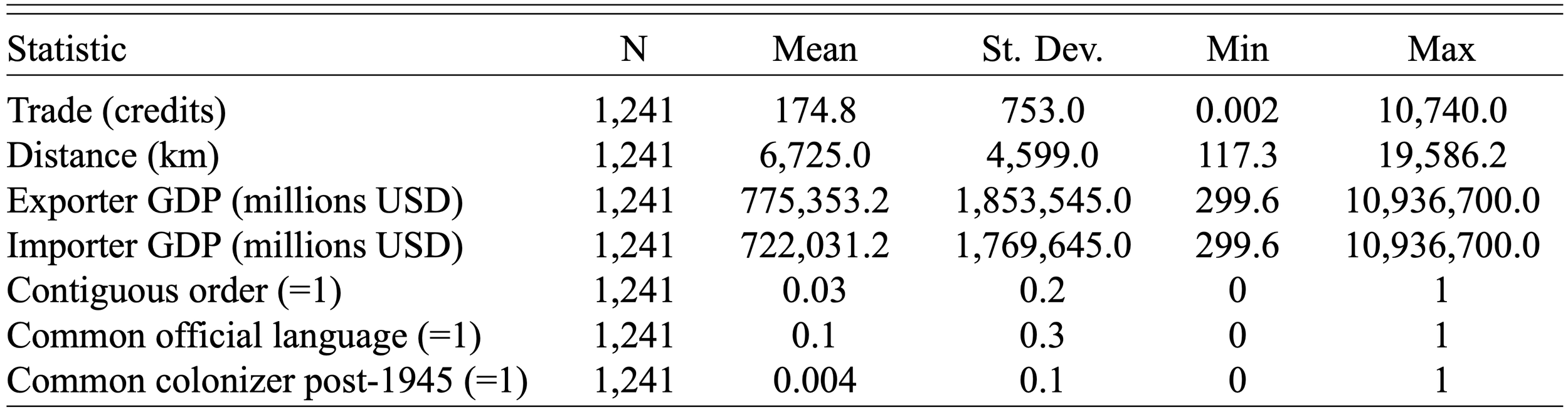

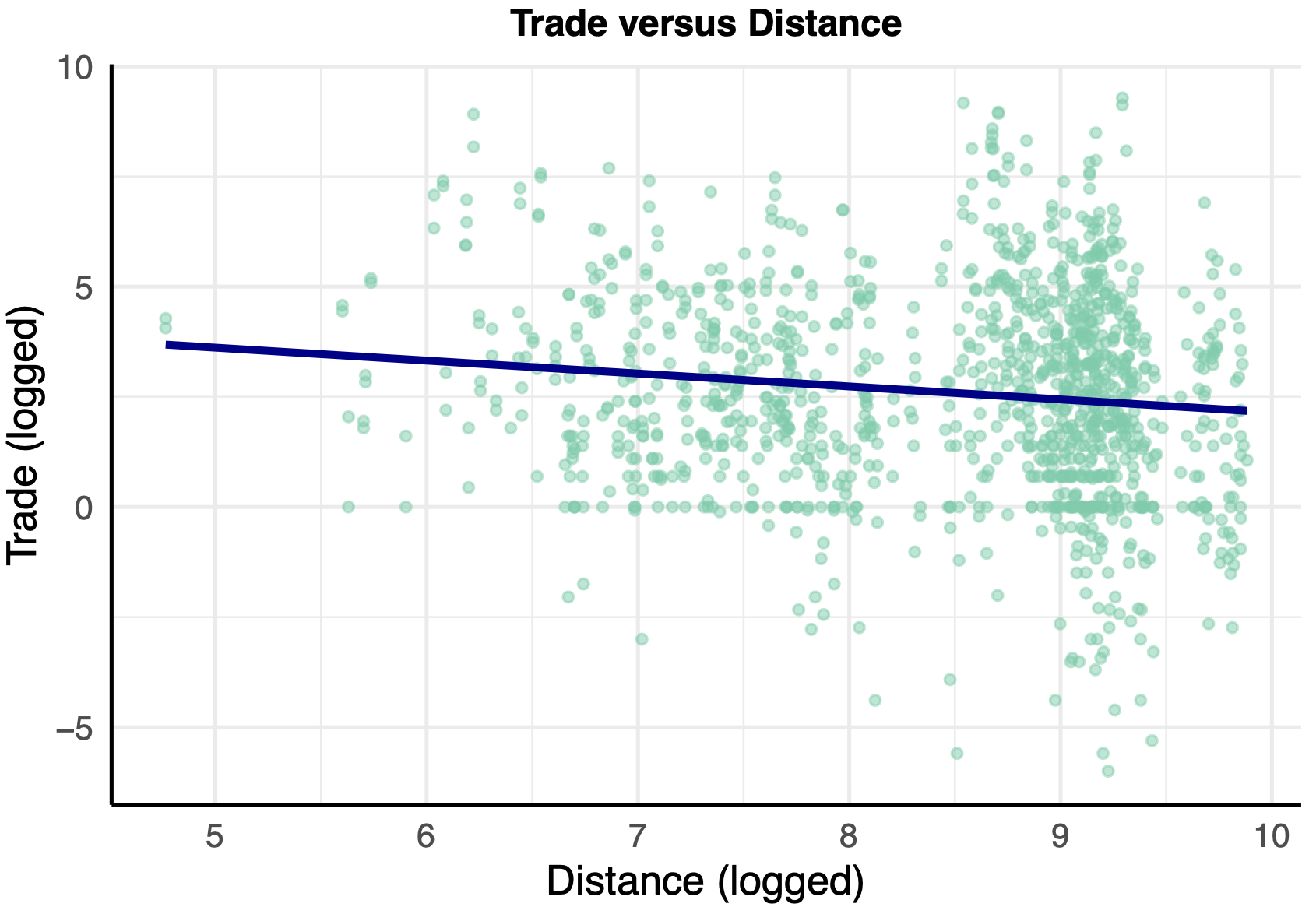

Trade values were highly skewed. Average bilateral trade was modest, but the distribution exhibited a long right tail, reflecting a small number of country pairs with extremely large services exchanges. Distance varied widely, from neighboring economies to pairs separated by nearly 20,000 kilometers, setting the stage for classic gravity-model forces to operate.

Visual Intuition: Distance, Size, and Shared Characteristics

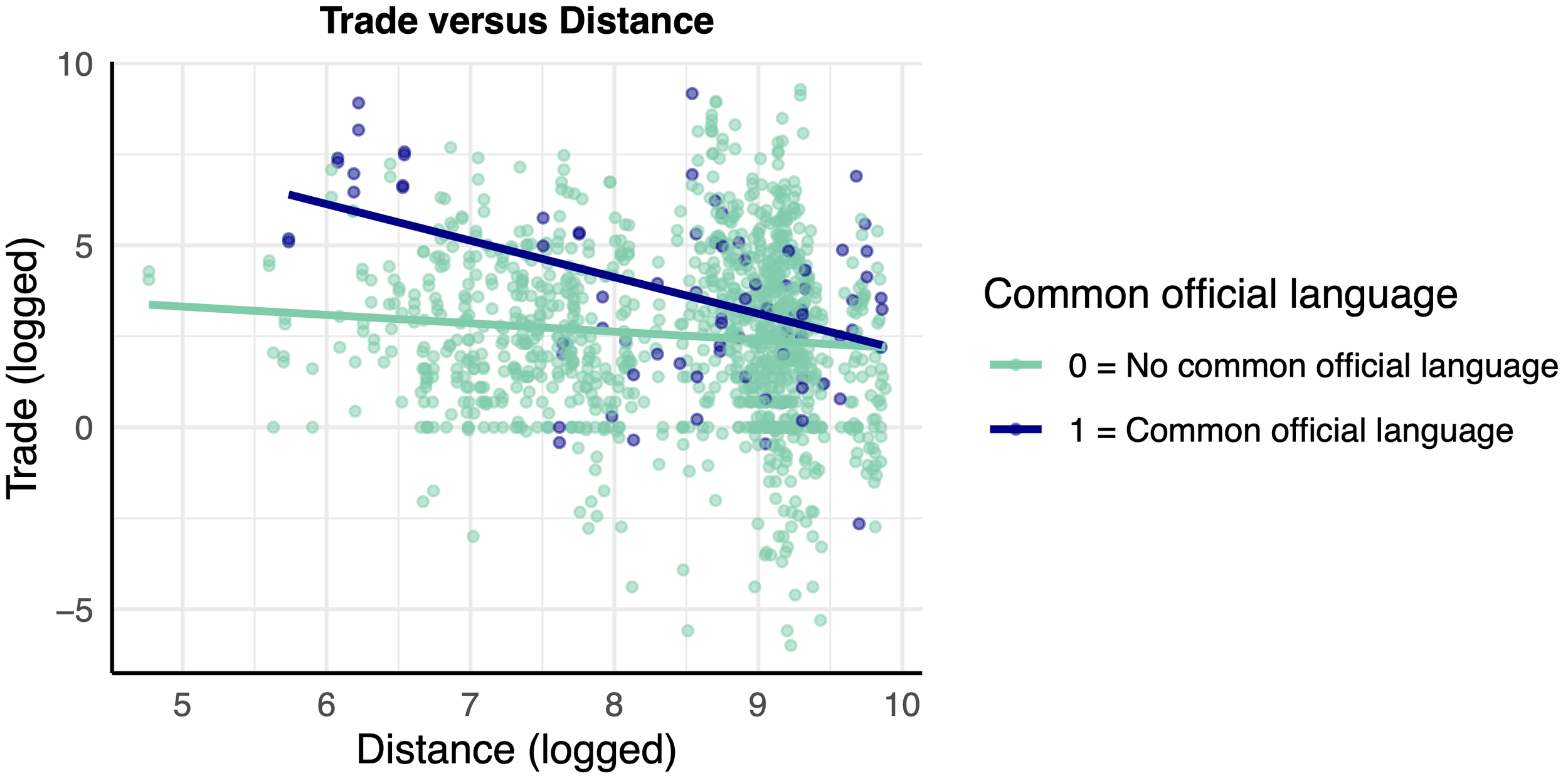

Before turning to regressions, I explored the raw correlations. Two patterns emerged clearly. First, distance is negatively related to trade, though the relationship is relatively weak at the raw-data level. Second, economic size dominates; trade rises sharply with the combined GDP of trading partners, consistent with gravity theory.

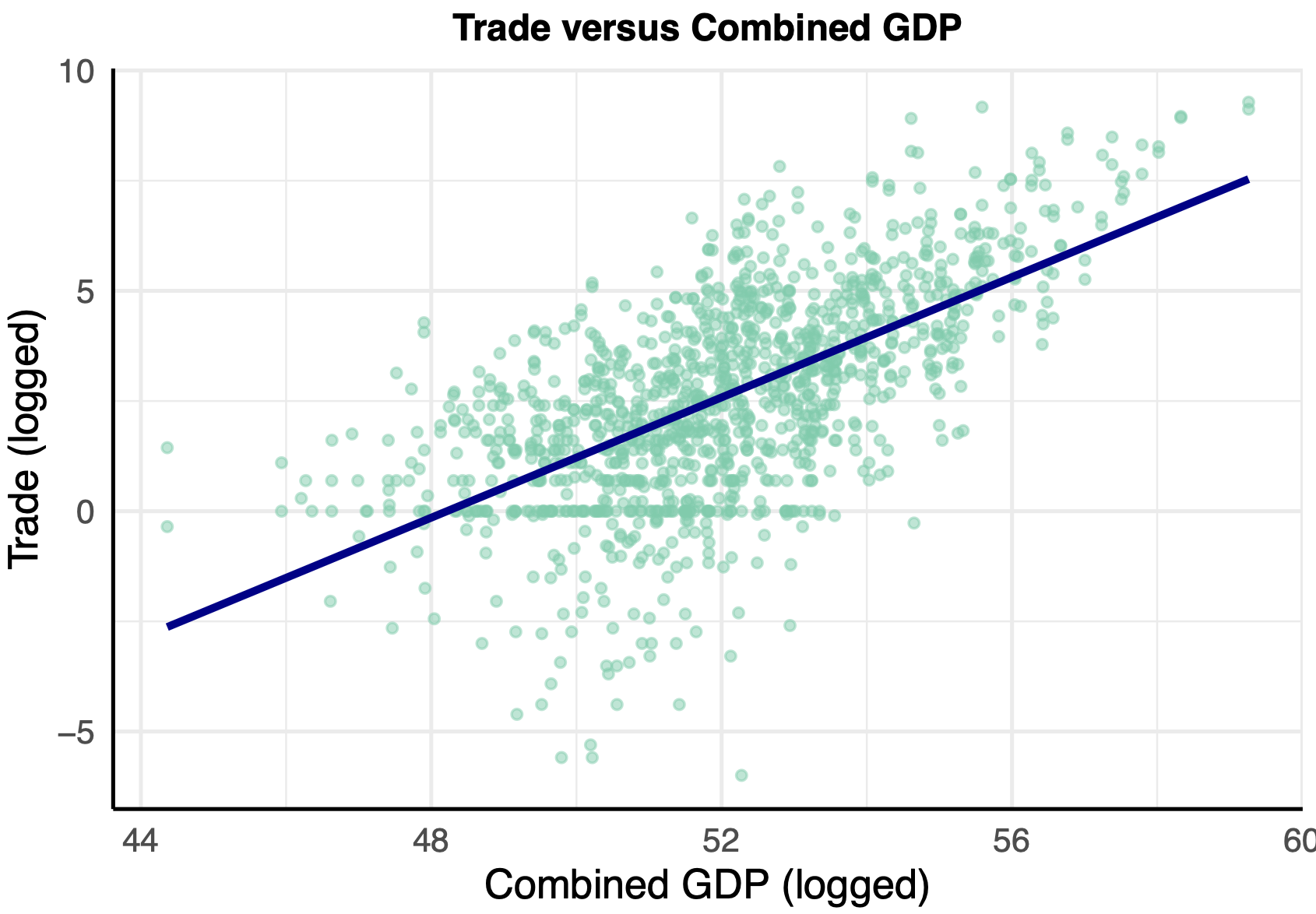

Clustering the data by shared characteristics adds nuance. Countries sharing a border or a common official language tend to trade more at comparable distances and GDP levels. Language effects are particularly strong at shorter distances, suggesting that communication frictions matter most when other barriers are already low.

The Intuitive Gravity Model

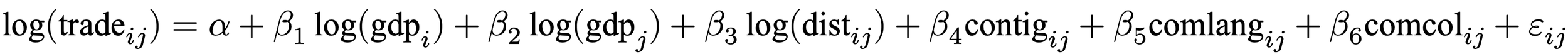

The first econometric model below estimates the “intuitive” gravity model, where trade depends directly on exporter GDP, importer GDP, distance, and a set of bilateral indicators. The results strongly support core gravity predictions. Both exporter and importer GDP enter positively and with high statistical significance, while distance exerts a large and negative effect: a 1% increase in distance is associated with nearly a 1% reduction in business services trade.

Among bilateral characteristics, common official language stands out as economically and statistically significant, implying substantially higher trade volumes between linguistically aligned partners. Contiguity and colonial ties, while positive, are not individually significant in this specification. Jointly, however, these indicators matter (F-statistic of 15.56, p < 0.01), suggesting that institutional and historical proximity still plays a role even if no single channel dominates.

The model explains roughly 56% of the variation in trade flows without accounting for fixed effects.

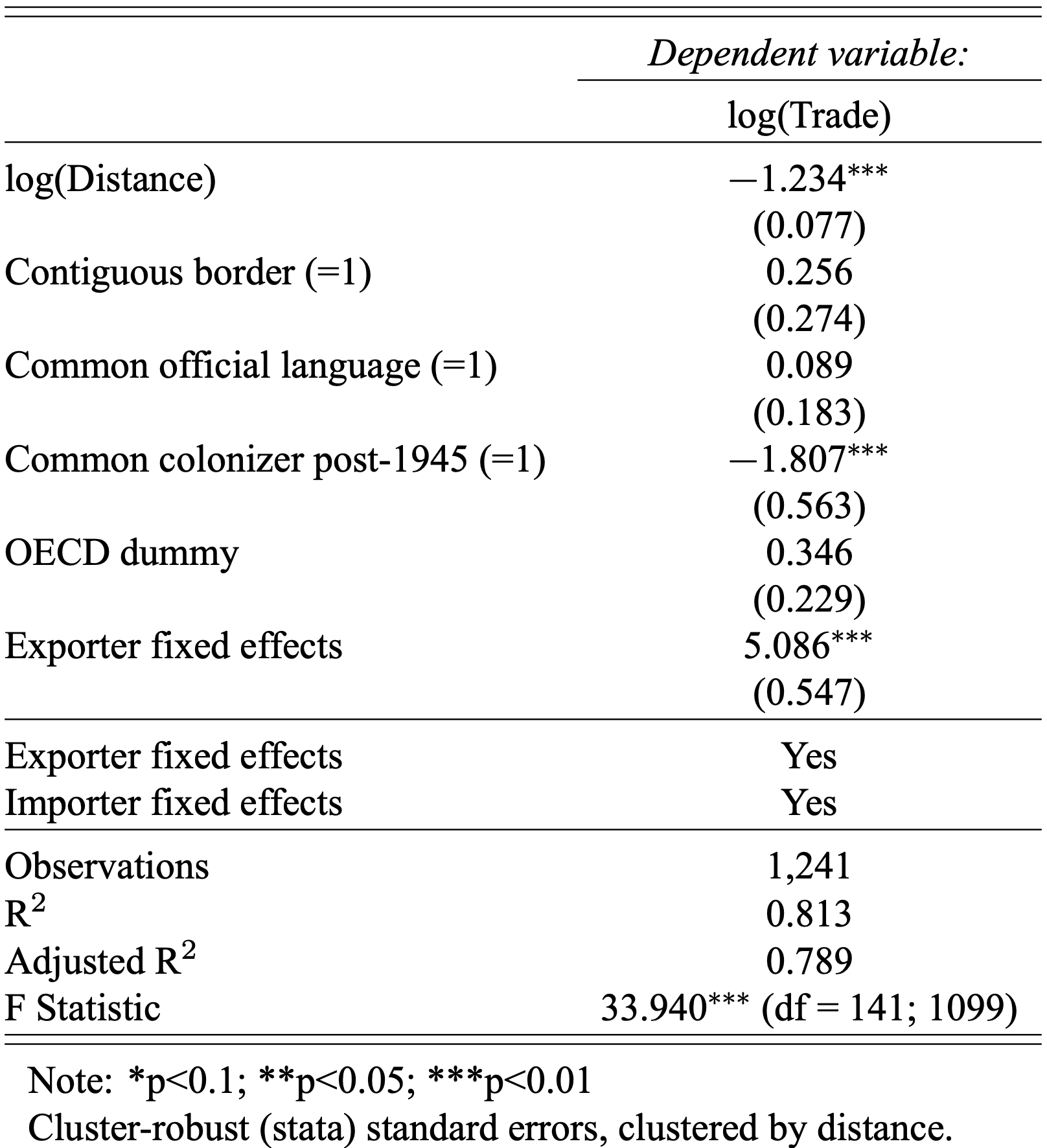

The Structural Gravity Model with Fixed Effects

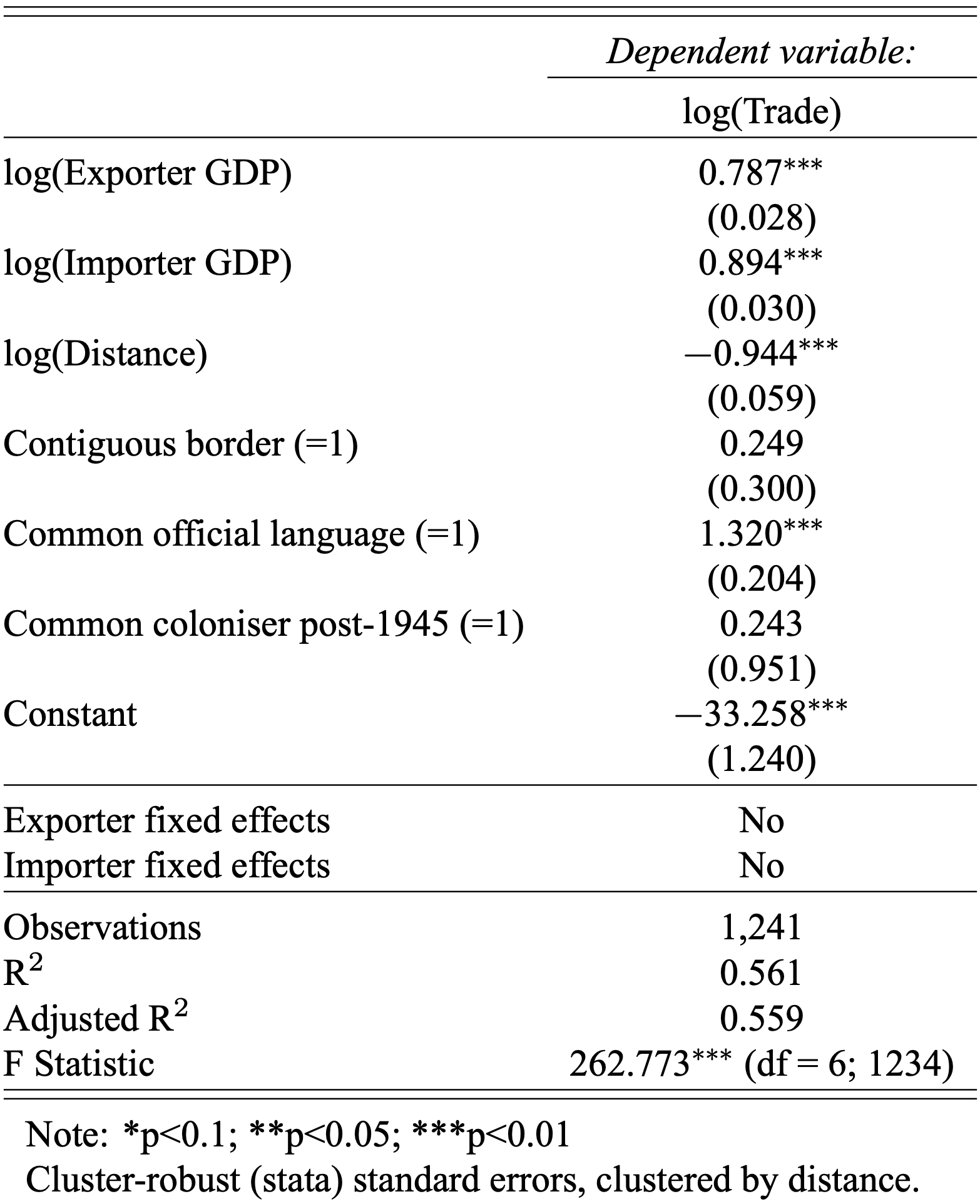

The analysis then shifts to a structural gravity model, replacing GDP variables with exporter and importer fixed effects. Conceptually, this absorbs country-specific characteristics such as economic size, productivity, and general openness, allowing the remaining coefficients to be interpreted more cleanly.

The improvement in fit is striking. The adjusted R² rises to nearly 0.80, indicating that much of the variation in services trade is driven by country-level fundamentals rather than pair-specific dynamics. Distance remains negative and highly significant, reinforcing its central role even in services trade. By contrast, the coefficients on contiguity and common language shrink and lose significance once fixed effects are included.

One surprising result is the negative and significant coefficient on common colonial history in the fixed-effects specification. This suggests that, conditional on modern country characteristics, historical colonial ties do not necessarily translate into stronger contemporary services trade—and may even reflect legacy structures that are no longer trade-enhancing.

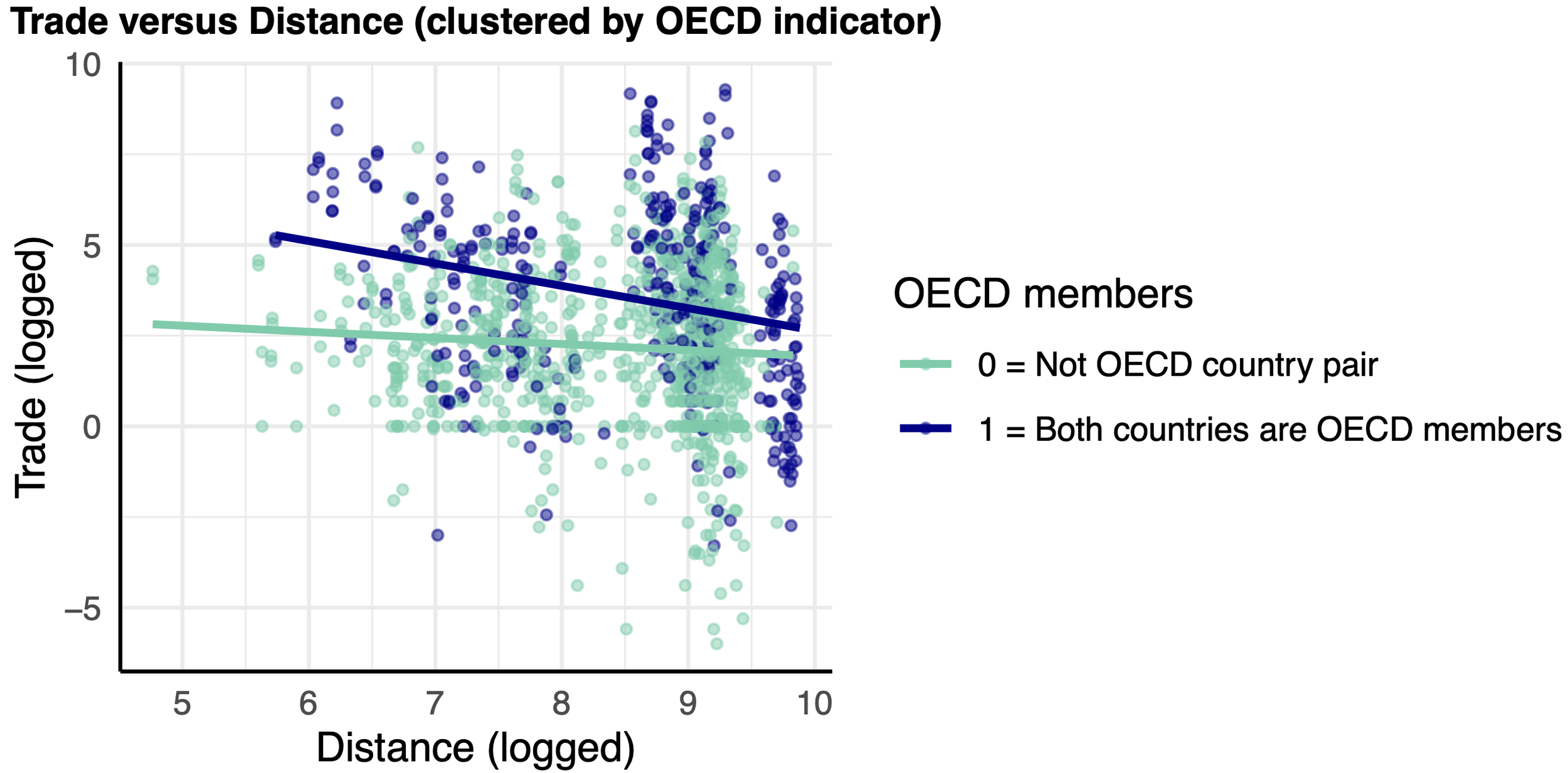

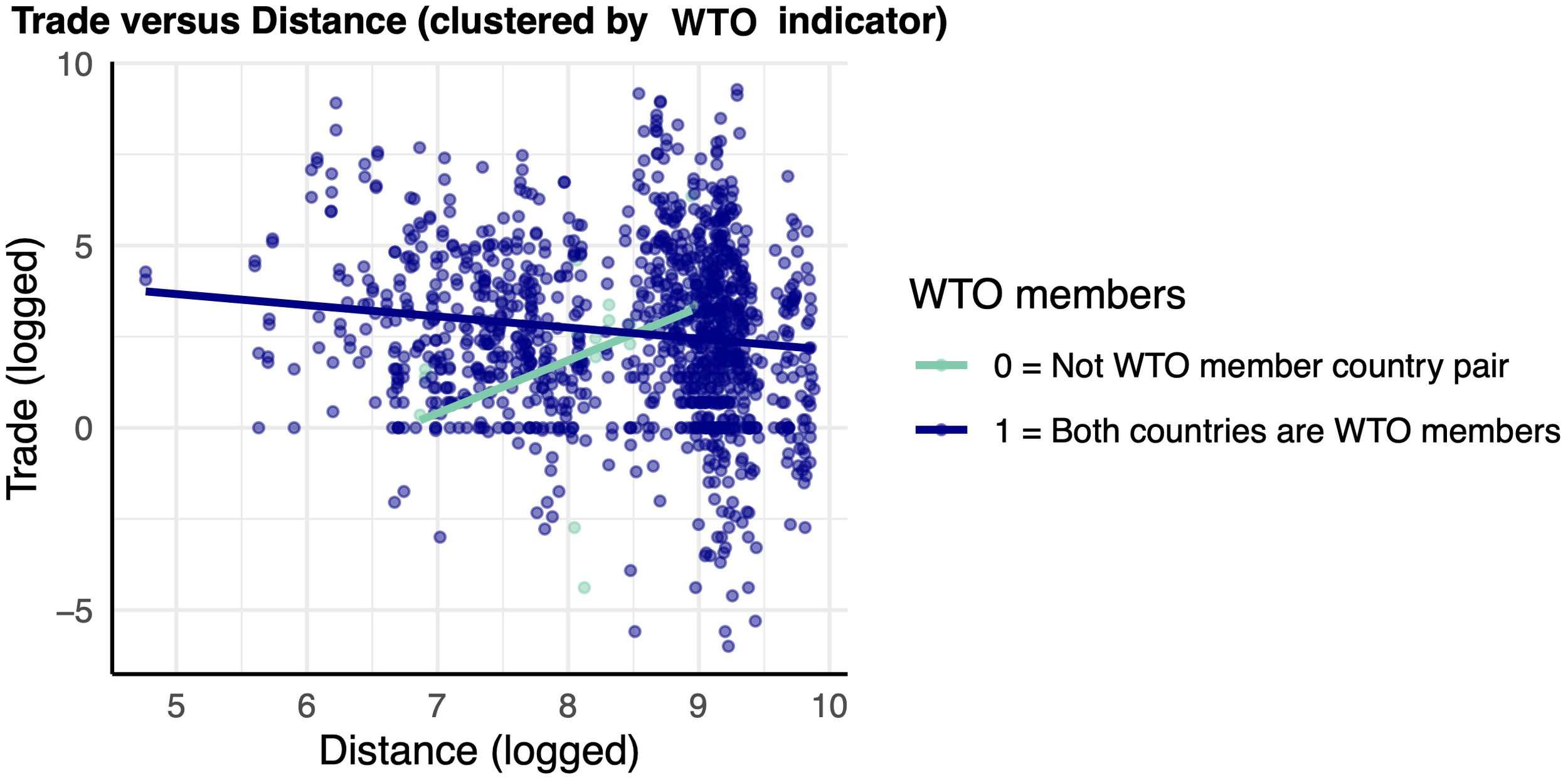

Measuring the Effect of OECD and WTO Membership

To explore policy-related channels, I augmented the structural model with indicators for OECD and WTO membership. Descriptively, OECD country pairs trade substantially more than non-OECD pairs at nearly every distance. However, once fixed effects are included, the OECD coefficient becomes statistically insignificant, suggesting that higher trade among OECD members reflects underlying economic characteristics rather than membership itself.

The WTO results are even more instructive. While raw averages show higher trade among WTO members, the regression produces a large negative coefficient. Nearly all countries in the sample are WTO members, leaving very few non-member pairs, which are disproportionately composed of sanctioned or politically isolated economies. The coefficient therefore captures exceptional cases rather than the true effect of WTO participation.

Interpretation and Contribution

This project reinforces a central insight of modern trade economics: economic scale and distance remain the dominant forces shaping trade, even in business services. Shared language and borders matter descriptively, but much of their explanatory power disappears once country-specific fundamentals are controlled for. Policy memberships such as OECD or WTO status correlate with trade intensity, but they do not deliver clean causal effects in a cross-sectional setting.

Methodologically, the analysis demonstrates why structural gravity models with fixed effects are now the benchmark in applied trade research. They prevent over-attributing trade flows to policy indicators that are themselves endogenous to development and openness. Substantively, the results caution against simplistic interpretations of institutional membership as a lever for increasing trade without addressing deeper economic fundamentals.

Conclusion

Business services trade is global, but not universal. While all countries participate, meaningful trade relationships are concentrated among a subset of partners linked by size, proximity, and institutional compatibility. Gravity forces continue to operate strongly, even in a global economy increasingly defined by intangibles.

This project shows how combining descriptive analysis, visualization, and progressively richer econometric specifications can separate correlation from structure. The takeaway is that policies and institutions matter, but they operate through—and are constrained by—underlying economic scale and geography rather than overriding them.